From time to time we hear organizations express dissatisfaction with KAP surveys. We often hear people saying they don’t work well. I once even heard a senior UN official say, ‘I don’t believe in surveys, period’. Can this be true or is something else at play?

Before talking about KAP surveys, let’s first look at surveys in general. We know for a fact that opinion polls are carried out to predict election results. It is one of the few instances where you actually have a chance to directly verify survey results with ‘real’ outcomes. While based in Indonesia, I had the opportunity to conduct a fair bit of polling research in the lead up to the 2004 and 2008 presidential and general elections. The tracking polls we deployed had an 8-day turnaround using face-to-face interviews and covered just under 80% of the population. The sample was no more than n=1500. Yet, our predictions were very much in line with other polls and the final election results were predicted within a margin of 3 percent. It would be fair to say that surveys do work and can predict results with quite a bit of accuracy, even under less than ideal conditions.

So what about KAP surveys, why do they sometimes fail to impress?

Having conducted KAP surveys in over 20 countries and across a number of thematic areas, I have found that the secret lies in preparation and execution. KAP surveys can be done as part of an initial program assessment or to look at impact and behavior change. It is in the latter case where results are likely to become more unpredictable as the expectation is to see evidence of real change. If the results prove otherwise there will be disappointment all around.

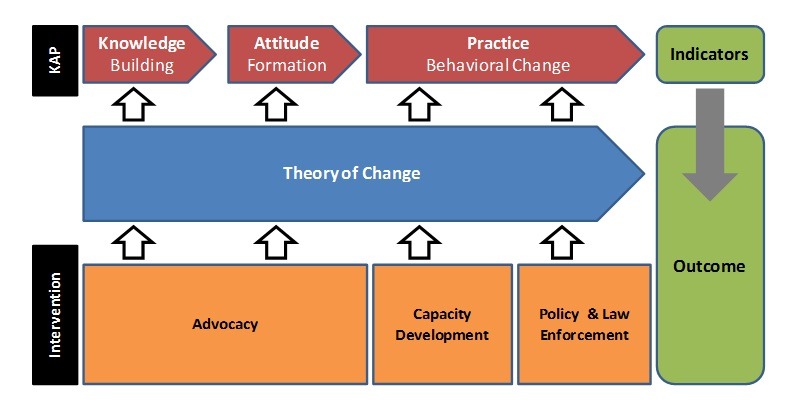

During the preparation phase, a key success factor for ensuring useful results from a KAP survey is to establish a strong link between what is measured in the survey and the program itself. This is easier said than done and, if based on intuition alone, things may not turn out so well. KAP surveys are often outsourced, resulting in the execution being in the hands of people without first-hand knowledge of the program itself. Hence, there is a need for clarity around how we translate program activities into a survey tool that can yield valid results. The framework outlined below can be a useful tool for how this can be accomplished. Note that the mediating factor between the program and the KAP measures is the theory of change. If a theory of change has not yet been established, this should be done first. The KAP should focus on the theory of change, not the activities of the program per se. What we need to measure in relation to program activities are things like awareness, exposure, relevance, and participation. For the KAP, however, the focus needs to be on how we expect our target audience to change in terms of adopting new knowledge, attitude formation, and behavior.

This may sound simple but in practice it can be quite tricky to fit all the pieces into the framework. It is an iterative process and conducting this exercise in the form of a workshop can work well, especially if the theory of change has only recently been established or if the program is entering into previously unknown territory.

This is but a first step to get a KAP survey off to a good start. Execution is another critical component and will be covered in a future blog. Know anyone who is conducting a KAP survey? Share this blog with them if you found it useful.

About the Author: Daniel Lindgren is the Founder of Rapid Asia Co., Ltd., a management consultancy firm based in Bangkok that specializes in evaluations for programs, projects, social marketing campaigns and other social development initiatives. Learn more about our work on: www.rapid-asia.com.