Programs or campaigns directed to change human behavior need to consider the potential influence of social norms. But what exactly are social norms, how do we measure them, and what are the potential implications for the program or campaign? The following are some simple guidelines that may be helpful when addressing these questions.

The existence of strong social norms can influence people to behave against their own better judgement, or what they believe to be right. In such cases, influencing people to change their behavior may be less effective unless social norms are tackled as well. Consider the following examples:

- Refusing to try shark fin soup at a Chinese wedding

- A teen saying ‘no’ to a cigarette when everyone else is smoking

- Breast-feeding in public

It is quite easy to see how social norms may come into effect in these situations. But what about the following:

- Using safety helmets when riding a motorcycle

- Using a mosquito net in a malaria prone region

- Applying safety measures when migrating for work

In these circumstances, the influence of social norms may be less obvious and could also depend on the particular situation. Hence, there is a need to measure the extent to which social norms play a determining role, and if so, are they more likely to affect some people more than others? A good way to measure this is to consider two key dimensions in connection to the desired behavior we would like to promote. The first dimension looks at whether the desired behavior would be considered socially acceptable (i.e. would others think it is OK?). The second dimension measures whether the desired behavior would be considered a normal behavior (i.e. do others behave in the same way?).

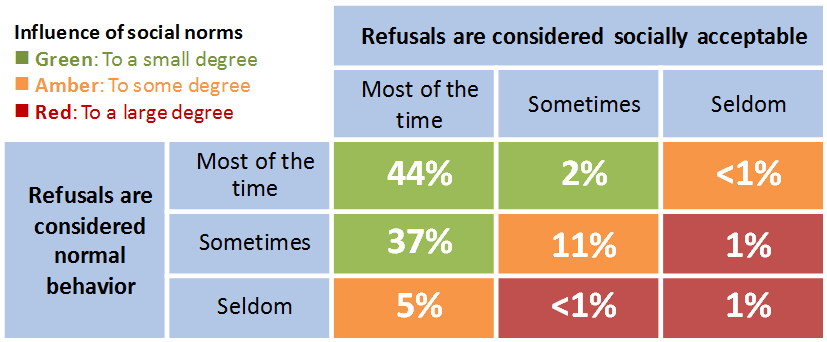

A case study on safe migration can illustrate how this works. One of the major risk factors is trafficking, where fake recruiters use deceitful tactics to trap and exploit migrants. Social norms can come into play if people feel it would not be socially unacceptable to refuse a job offer, even if they felt unsure about the agent or the work itself. To test this, potential migrant women in Maguindanao (Philippines) were asked to determine whether (1) refusals were considered socially acceptable and (2) whether refusals were considered to be normal behavior. The matrix below shows how the answers were distributed when combining results for the two questions. Some 83 percent indicated that social norms only slightly influenced their ability to refuse a job offer from someone they didn’t trust. So, in this case, the influence of social norms was considered to happen only to a small degree.

Figure 1: Measurement of Social Norm and Interpretation

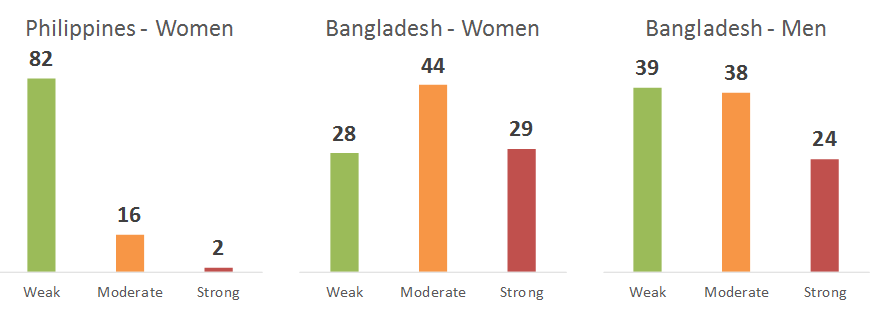

Likewise, a similar study was done with potential migrant women and men in Bangladesh. In this study, the results indicated social norms cannot always be ignored, especially for women. In the case of Bangladesh, 29 percent of women indicated that social norms strongly influence their ability to refuse a job; however, for men it was somewhat lower with 24 percent. Further analysis showed that women in the Philippines largely decided for themselves whether or not to migrate, whereas in the case of Bangladesh influence from family members was much stronger. That is to say, social norms were stronger in Bangladesh compared to the Philippines.

Figure 2: Social Norms Vary by Country and Sex

These results show that it is not possible to generalize when it comes to social norms. Sometimes they are vital, and sometimes they are less relevant. In some cases, they affect certain sub-groups more than others. The implication for initiatives directed to influence safe migration behavior is that in the Philippines, efforts to change behavior at the personal level can be effective, provided other barriers don’t exist or can be overcome. In Bangladesh, on the other hand, initiatives need to consider key influencer groups as well (i.e. Family members). Further, qualitative research, to better understand how those influences manifest themselves, may also be warranted.

If you found this article useful, please remember to ‘Like’ and share on social media, and/or hit the ‘Follow’ button to never miss an article. You may also want to read this article on Measuring Behavior Change, Effectively.

About the Author: Daniel Lindgren is the Founder of Rapid Asia Co., Ltd., a management consultancy firm based in Bangkok that specializes in evaluations for programs, projects, social marketing campaigns and other social development initiatives. Learn more about our work on: www.rapid-asia.com.