Mixed-method approaches are becoming more popular in the world of evaluations. Preceded by a desk review, a survey may be coupled with key informant interviews and focus group discussions. The argument for using mixed methods is that results can be verified by more than one data source. But how do we analyze the data? Well, we need to triangulate. This is where things become complicated.

Most practitioners have a good idea of what triangulation means and why it is useful. However, results often fall short of expectations as we realize that triangulation may be more difficult than it seems. The problem often lies in the planning and design stages of the evaluation. Below are some simple tips on how to find our way through the jungle.

A complicating factor is that mixed-method evaluations are carried out in different ways. Data may be collected using different methods in parallel. This may become necessary when working with a tight time schedule. When time permits, a sequential approach is often preferred as what we learn from one data source can feed into the next stage. For example, a common design is to collect qualitative data to inform a subsequent quantitative survey. However, there are times when qualitative insights are needed to drill further into quantitative findings. Desk reviews and secondary data sources are often weaved into the design and the order of events really depends on the particular circumstances. There is no hard and fast standard. Regardless of the design, triangulation will be necessary to make sense of the data collected. If the data was collected by different people, which is often the case, another challenge emerges as no one person has full overview of all the data.

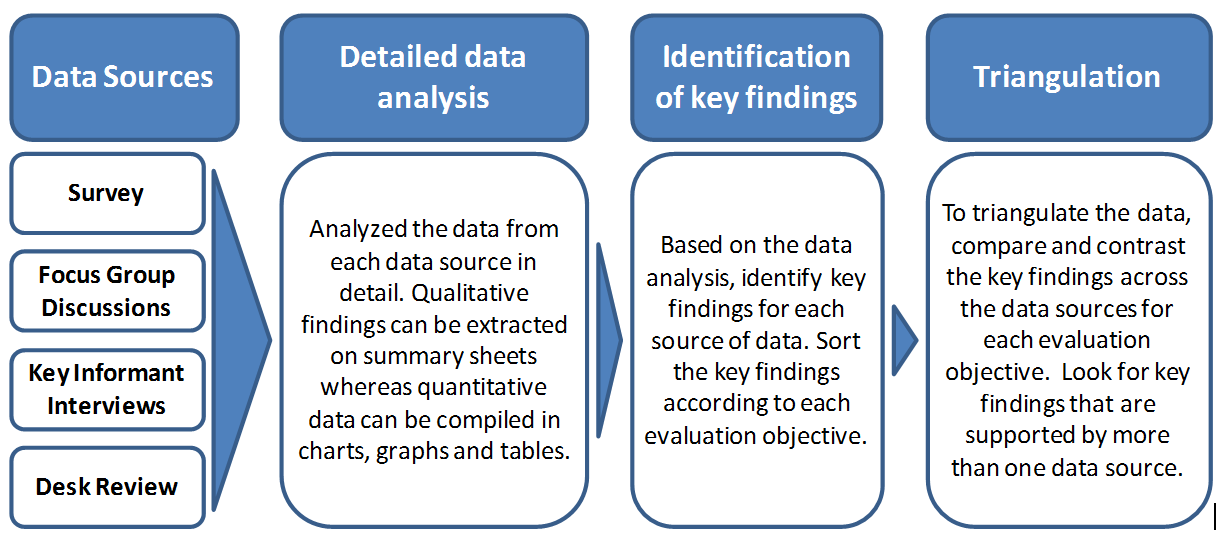

Below is a simple, three-step, approach that can be used to ensure consistency and make sure no evaluation objective goes unanswered.

As a first step, it is recommended to fully analyze each data source. This means producing summaries for qualitative data and data output in the form of charts, graphs, and/or tables for quantitative data. Data sources from a desk review should also be included. Second, once the data has been analyzed, key findings can be extracted. Findings need to be grouped and sorted according to the evaluation objectives. This is a tedious, yet necessary process, as the structure of the survey tools may not follow the same structure, or order, as the evaluation objectives, especially for qualitative data. Finally, when all the key findings have been sorted, the triangulation process can begin. This process should be relatively straight forward if the preparation work has been done properly. Looking across each data source, key findings that are similar can be more easily identified. Key findings can then be grouped into those that are substantiated by other data sources and those that sit on their own. At this point a clear picture of the result should start to emerge. To make the sorting and triangulation process more productive (and fun perhaps) it can be done as a team exercise. More eyes means quicker identification of what belongs where and some level of debate is always healthy.

It needs to be said that proper triangulation is not a substitute for poor quality data. If, however, the data is of poor quality, this form of triangulation process is likely to identify it in the form of data inconsistencies. The survey tools are also critical and will be the subject for a future blog.

Know someone who is working on a report? Pass on this blog and see if it can help them 🙂

Connect With Rapid Asia l Facebook l LinkedIn l Twitter l

About the Author: Daniel Lindgren is the Founder of Rapid Asia Co., Ltd., a management consultancy firm based in Bangkok that specializes in evaluations for programs, projects, social marketing campaigns and other social development initiatives. Learn more about our work on: www.rapid-asia.com.