Most of the migrants in Thailand are from Myanmar and have been coming to the country since the economic boom between 1987 and 1996. A recent study carried out by Myanmar Development Observatory (MDO)-UNDP in collaboration with Rapid Asia, explored current migration policies in Thailand and why they encourage employers to take risks of employing undocumented migrants.

Thailand’s impressive economic growth (nearly 10% per year) in the 1980s and 1990s attracted a large number of migrants from its neighbouring countries. During this time, Thailand transformed itself from a net-sending to a net-receiving nation for migrant labour. Thailand also experienced demographic changes with the lowest population growth rate (0.2% annually) and second-lowest total fertility rate (1.5 children per female) in Southeast Asia. Hence, the demand for migrant labour has continued until today.

A multi-stakeholder report focusing on Myanmar reported that as of April 2023, an estimated 2.5 million regular migrants resided in Thailand and 75% of them were from Myanmar. Furthermore, the latest report by the MDO-UNDP reveals that 37% of the 2,249 respondents (Myanmar migrant workers) were undocumented workers.

The report, titled “Seeking Opportunities Elsewhere: Exploring the Lives and Challenges of Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand”, outlines the details of the Royal Thai Government (RTG)’s commitment to the integration of Myanmar migrants through a series of policies. But, the report also points out some gaps in the support system for migrant workers.

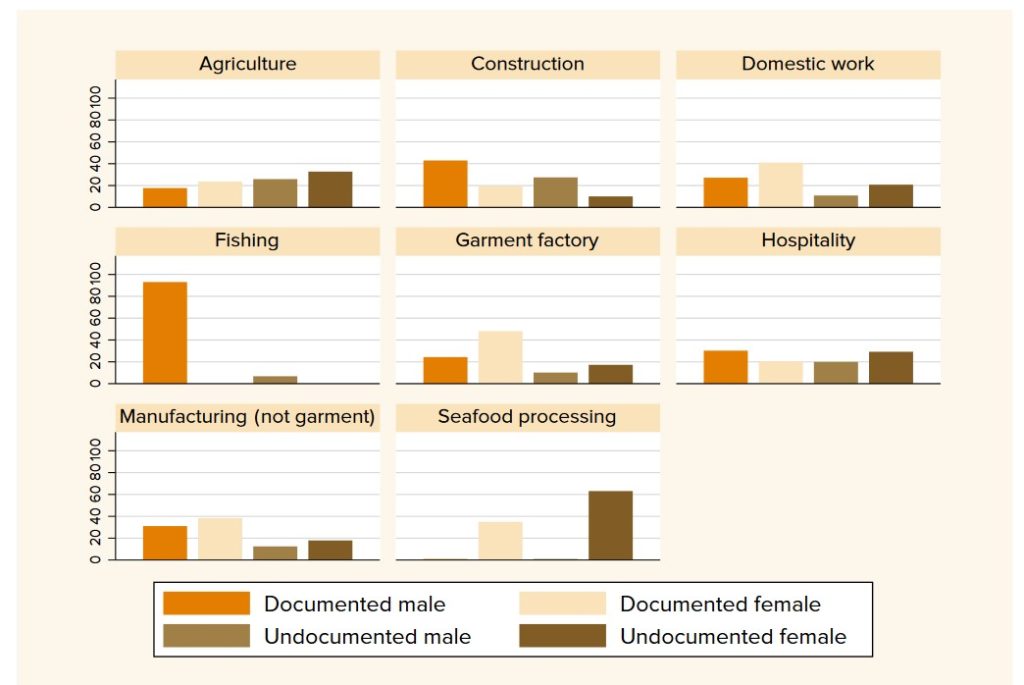

Figure 1 below shows the distribution of migrant workers (broken down by sex) across 8 different sectors in which undocumented migrants are most prevalent. These include agriculture (59%), hospitality (49%), and seafood processing (64%). A potential driver of informality is seasonal work, which is prevalent in the agriculture and hospitality sectors and causes these industries to readily absorb migrant (including undocumented) labour during periods of heightened demand.

Figure 1. Working Sector of Migrants

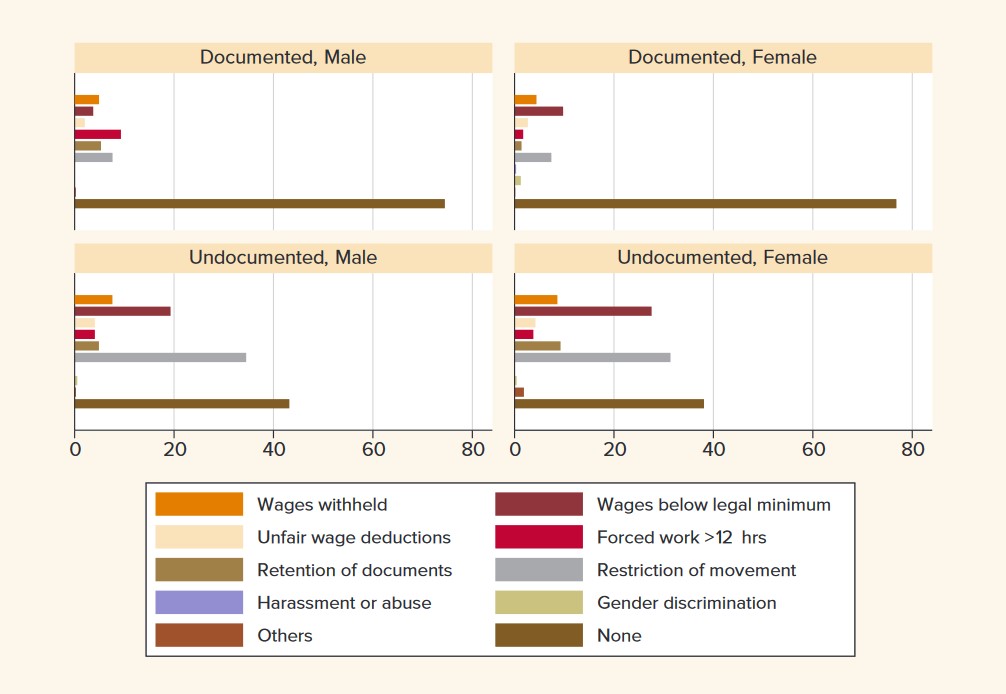

In addition, figure 2 shows how undocumented migrants are on average more disadvantaged when it comes to work conditions and work entitlements.

Figure 2. Issues experienced by the migrants while working in Thailand.

The study points to several policy issues where there could be an opportunity to better support migrants while promoting regular migration at the same time.

- Visa Options: significant surges in labour demand by employers that often go unmet and lead to employers taking additional risks to hire undocumented migrants, meanwhile there are also administrative inefficiencies. The MOU migration process also does not provide a legal channel for dependents which incentivises irregular family migration or forces parents to leave their children behind in Myanmar. This situation is exacerbated by a lack of information and available support.

- Healthcare Access and Mental Health Support: only 12% of undocumented migrants use public hospitals and 68% of undocumented migrants have not used any healthcare services. This unequal healthcare access is closely related to improper documentation and vulnerable legal status.

- Workplace Practices: undocumented Myanmar migrants are more likely to lack additional employment benefits.

- Family Unity: despite the Thai government’s steps to ensure access to essential services (e.g. education for migrant children), gaps remain between policy and its implementation.

- Gender Equality: gender discrimination exists with a lack of support structures and low awareness of workplace policies. They underscore the need for policy reform and interventions that are gender sensitive.

The report shows that increasing labour demand and evident gaps in Thai migration policies have encouraged employers to take risks of employing undocumented migrants. The report recommends remedying the situation through interventions that ensure that labour demand is met whilst migrants are safe, and free from exploitation, and can contribute to both Thailand and Myanmar’s development.

If you found this article useful, please remember to ‘Like’ and share on social media and hit the ‘Follow’ button never to miss an article.

To read more about seeking opportunities elsewhere: exploring the lives and challenges of Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand, please click here.

About the authors: Daniel Lindgren is the Founder of Rapid Asia Co., Ltd., a management consultancy firm based in Bangkok that specialises in evaluations for programs, projects, social marketing campaigns and other social development initiatives. Israr Ardiansyah is an independent consultant working with Rapid Asia.

Photo by Rio Lecatompessy on Unsplash