Photo credit: Mahmud Rahman

The Thai fishing sector has been under scrutiny in the recent years and the ILO “Ship to Shore Rights Project” has been working with the Royal Thai Government, unions, and employers to help improve work conditions for workers in the fishing and seafood sectors. A recent survey, conducted by Rapid Asia on behalf of the ILO, found that work conditions have generally improved over the past couple of years, but cases of forced labour can still be found. See also the full report .

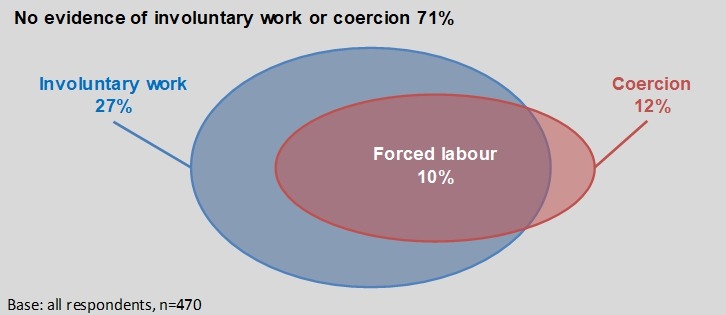

The ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29) defines forced labour as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily”. In the ILO framework, indicators for measuring forced labour are classified into indicators of involuntary work and indicators of coercion. Overall, 27 percent of workers surveyed in the Thai fishing industry had circumstances of involuntary work and 12 percent had experienced some form of coercion. A forced labour case is confirmed when indicators of involuntary work and coercion are both active, which was true for 10 percent of the workers surveyed as shown in Figure 1 below. The prevalence of forced labour among the workers surveyed was higher in the fishing sector with 14 percent compared to seafood with 7 percent.

Figure 1: Forced labour among workers surveyed in the Thai fishing industry

The more common circumstances of involuntary work involved living in degrading living conditions, working in a degrading work environment, and having limited freedom to leave the employer. These circumstances do not by themselves constitute a forced labour case unless the worker is coerced to stay. Coercion can be in the form of physical violence, but simply the threats of violence or being under constant surveillance also represent elements of coercion. In the Thai fishing industry, physical violence, sexual abuse, or harassment were less common. Instead, threats, restriction of movement, constant surveillance, withholding identify documents or mobile phones, and being locked up in the work place or living space were forms of coercion found to be more common.

Whilst this was not the first time forced labour was measured among workers in the Thai fishing industry, it cannot be said with certainty whether the situation has improved or not. However, there was evidence of improvement in other areas when comparing some of the results to the 2017 baseline survey, also carried out by Rapid Asia. For example, minimum wage compliance improved significantly and more than 90 percent of workers interviewed reported being paid minimum wage or more in both the fishing and seafood sectors. More workers are also receiving a monthly fixed salary. Illegal salary deductions were also found to have declined and more workers are receiving a written work contract.

Moving forward, reducing forced labour should be a key priority. But some questions have yet to be answered. For example, whether employers have adopted more covert methods to manipulate workers, particularly migrant workers. For example, while the study found that upfront recruitment fees for migrant workers had come down drastically, there was anecdotal evidence from interviews with various stakeholders that recruitment fees are no longer paid up front and but used by employers as debt bondage. The worker may not know this until such time they want to leave and could find themselves trapped. This form of coercion can be difficult to detect but shows how forced labour may have evolved over time from a blunt tool of physical abuse to a more subtle instrument, but with the same devastating effects.

Considering that employment conditions are generally improving, and that the Thai government continues to reform the industry in order to improve labour conditions, it should be possible to eradicate forced labour within the near future.

If you found this article useful, please remember to ‘Like’ and share on social media, and/or hit the ‘Follow’ button to never miss an article.

About the Author: Daniel Lindgren is the Founder of Rapid Asia Co., Ltd., a management consultancy firm based in Bangkok that specializes in evaluations for programs, projects, social marketing campaigns, and other social development initiatives. Learn more about our work at www.rapid-asia.com.